Optics

Photons are the new golfballs

An important aspect of both ion simulations and real ion flight is that the ion trajectories are relatively deterministic. Given the same initial positions, velocities, masses, and charges as well as exposure to the same electric fields, the trajectories of multiple ions will be identical. Multiple ion trajectories can be thought of much like a beam of light and like a beam of light, we can use lenses and optics to focus, defocus, reflect, and disperse ion trajectories.

Like the other analogies, thinking of ion trajectories as beams of light breaks down eventually. First, ions cannot pass through the electrodes of a lens, but in most cases light enters the solid lens material. Light is not affected by optical materials before it enters them, but ions “feel” the effects of an electrical gradient at a distance from the electrode. Second, the kinetic energy “spread” of ions is often much greater than the energy spread of light. For example, visible light ranges from around 1.7 to 3.3 eV of energy — a 2× spread. Charged particles can have kinetic energies ranging from 0 eV (motionless) to trillions of eV where relativistic effects take place. Large energy differences in ions can lead to difficulty in focusing, which is one reason why ions are often accelerated — to reduce the relative differences between them. Third, charged particles can have effects on other charged particles or surfaces — for instance, by repelling one another or inducing a surface charge. Fourth, charged particles are simply not light, so effects like metastable decay can occur with ions; light exhibits wave-like properties (e.g., coherence); and light cannot be trapped in the same way as charged particles.

Still, the analogy holds well enough that vocabulary is shared between light and ion optics and there are ion optical analogs of most light lenses. One such analog of a simple convex lens (found in magnifying glasses and reading glasses over the world) is the einzel lens.

The Einzel lens

Varying diopters has never been this easy

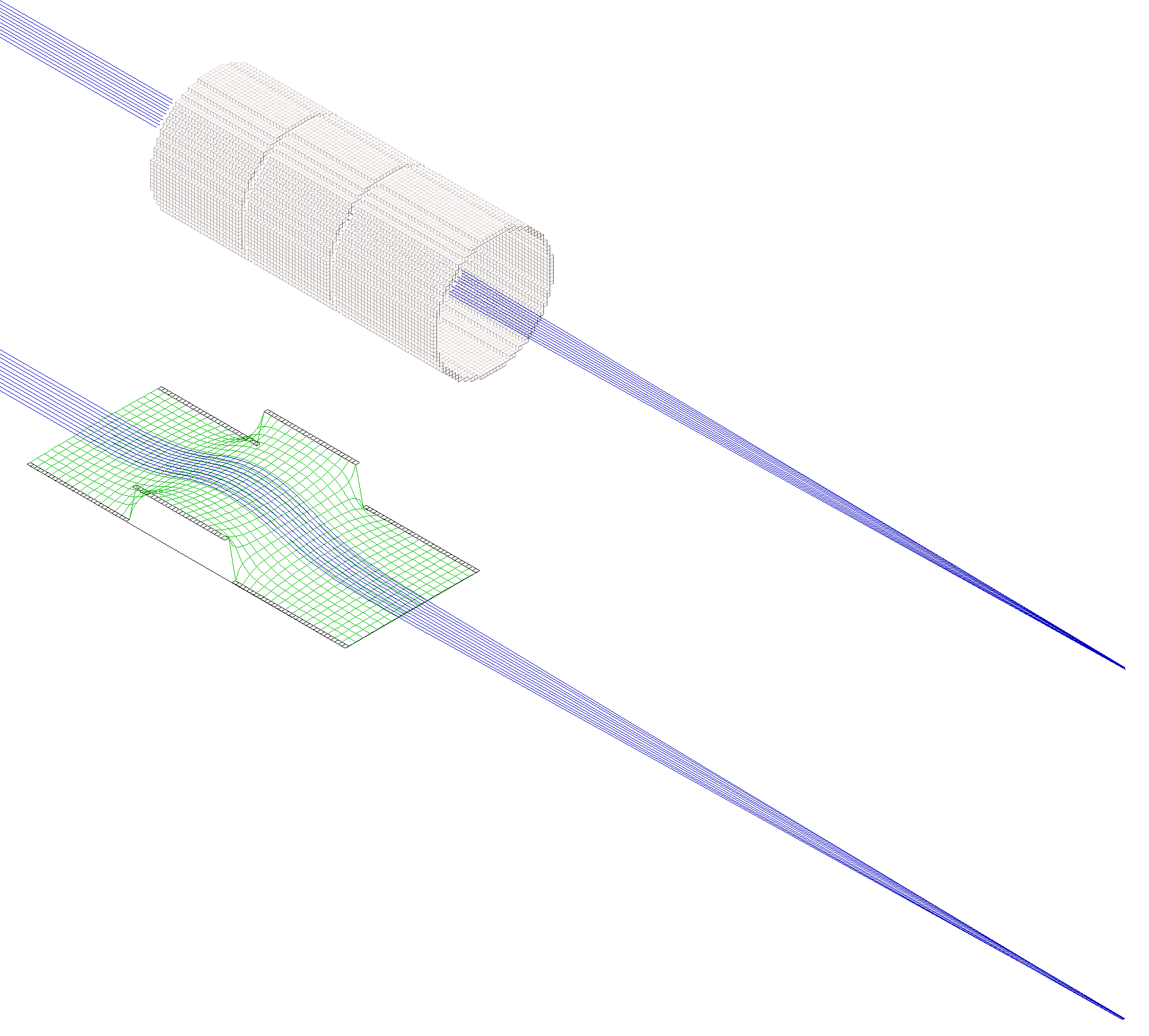

The image below shows two views of SIMION’s einzel lens example. The top view shows the 3D voxels that make up the simulated einzel lens. The bottom view shows a potential energy surface like the one we saw in the section on visualization. Both views show the ion trajectories of the ions that start in the top-left side, fly and are focused toward the bottom-right. An einzel lens has three cylindrical electrodes (sometimes these are square cylinders rather than circular). The outer two electrodes are kept at a low voltage — usually 0 V. The inner electrode is raised to some potential — in the SIMION example, 110 V.

The potential energy surface shown in the lower view helps to demonstrate the focusing effect intuitively: the ions enter parallel to one another but the “saddle” shape caused by the electric field causes the ions to expand slightly near the apex and then begin to contract as they move down the potential surface, focusing the “beam” of their trajectories.

Although the SIMION example is fully 3D, the ion physics work identically for an einzel lens in 2D as it is radially symmetric. The similarities of the SIMION example to the Simulation Playground example should be clear:

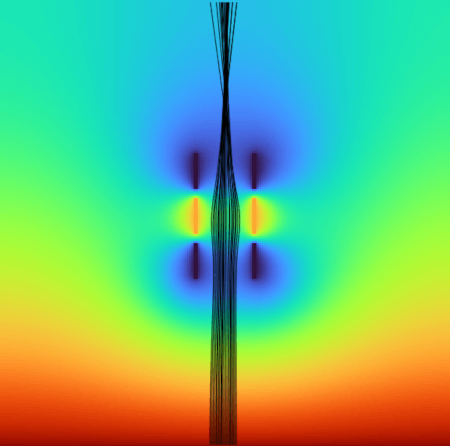

Here, ions are flown from the bottom of the simulated field to the top. The ion kinetic energy is generated by an electric gradient from an electrode (initially set to 100 V) at the bottom. Unlike the SIMION simulations in the images above, the ions continue on after their focal point and begin diverging just like rays of light would diverge in a concave lens. Also, the focal point is not as clearly defined as it is for the SIMION simulation.

Einzel lenses work for both positive and negative ions — but for negative ions the polarities of the lenses need to be reversed.

Many einzel lenses are intended to be operated in positive and negative modes and to be calibrated, so their voltage can usually vary, just not on the timescales of ion flight — recalibration of ion optics is sometimes necessary because the electrodes become dirty over time as errant ions or neutral molecules impact the electrode and stick to it. Over time, the effective electric field changes as a result of the dirtying of the optics and slightly different voltages need to be applied. Eventually, most ion optics must be cleaned — however this can take time, requires “venting” the vacuum chamber, and can potentially damage the electrodes.

As their voltages do not vary over the course of an experiment, einzel lenses are considered electrostatic ion optics. This makes simulating them especially easy but it also means that ions do not gain or lose energy (assuming no friction or collisions) while interacting with an einsel lens. As the ions move over the “saddle” point, they lose kinetic energy but gain a corresponding amount of potential energy. After the ions leave the einzel lens, they have the same kinetic energy that they entered the lens with.